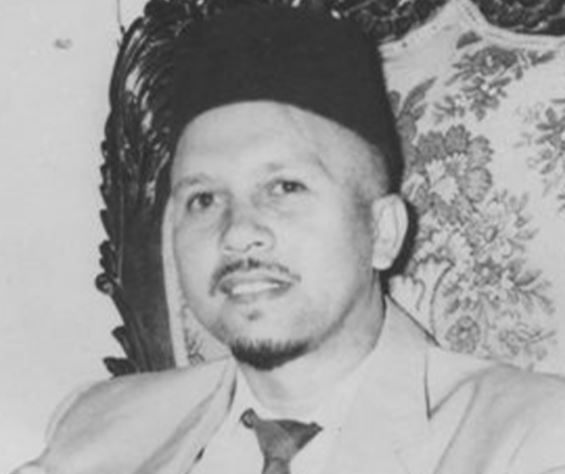

The reopened inquest into the death of anti-apartheid cleric Imam Abdullah Haron heard the testimony of how he was coldly fired while being held in detention without trial, and how his family lost their house after he died.

During a moving morning at the Western Cape High Court on Thursday, his son, Muhammed Haron, told presiding Judge Daniel Thulare his father tried to assure them that he was okay while in detention and under interrogation by apartheid Security Branch police officers.

He told the court that if they stood on the pavement outside the Cape Town Central police station, where his father was hel if they shouted loud enough, there was a chance he might hear them from his cell.

One day, he stood outside and shouted a greeting to their father, who was detained there without trial between May and August 1969.

“He shouted back, ‘Moenie worry nie. Is orrait’,” said Muhammed.

The assurance in Kaaps translates to “Don’t worry, everything is alright” – but everything was not alright.

The imam was arrested in Cape Town on 28 May 1969 by a policeman who had blended into the long line of people waiting to talk to the imam at his home in Cape Town.

Muhammed said his father’s life’s duty as a Muslim was to always be a helping hand to those in need, regardless of their background. So, when the police told them their father was being arrested for terrorism, they were shocked.

Muhammed asked: “I mean, this man who is doing good for his fellow human beings, how can he be described as a terrorist?”

He explained that his father devoted every waking hour to helping people.

His father’s work included helping to distribute assistance to the families of political detainees left destitute if a breadwinner was in custody. Those under banning orders could not even go out and work, so they had no income to pay for rent or food.

Besides being an imam, his dad was also a sales rep for sweets company Wilson Rowntree. Because of his travels as a salesman, he did not need the dreaded pass to visit Nyanga and Gugulethu.

In the Western Cape at that time, the PAC was more active than the ANC, so through his work of helping people in need, his father inevitably came into contact with PAC political leaders, who asked him to deliver food and money to people in Nyanga and Gugulethu.

From there, he became connected to political networks, which resonated with his sense of social justice, and he was not afraid to speak out against apartheid in his sermons and public addresses.

But his arrest turned their lives upside down.

Earlier in the inquest, the imam’s daughter, Shamela Shamis, read a letter from her father which was smuggled out of the police station in a vacuum flask. He had already sent her to London for her safety, and it was sent to her there.

She tearfully read out his letter to her, written on the back of an old cream cracker packet, where he broke the news of his detention.

An extract read: “Don’t worry, it’s for a good cause.”

After his arrest, many friends from the mosque were also taken in for questioning, and people became suspicious of each other in an era of possible informants.

While he was in detention, his employer Wilson Rowntree sent him a cold and impersonal letter in prison firing him, attaching a cheque of R492 owed to him.

After months in detention, including solitary confinement, on 28 September 1969, two Security Branch policemen – Major Dirk Kotze Genis and Sergeant Johannes “Spyker” van Wyk – arrived at their house in Athlone.

It happened to also be the day that Muslims marked the birthday of the Prophet Muhammad.

“When the Security Branch comes to your door, you know it is not good news,” said Muhammed, choking back tears.

The policemen told them their father was found dead in his cell at Maitland police station on 27 September.

Muhammad broke down and cried on the witness stand as he recalled the day that their lives changed profoundly. The family was told that he died after falling down steps, but they never believed that.

When the family finally received his body from Salt River mortuary on the Monday, fresh trauma awaited them. When they lifted the shroud to wash his body per Islamic rites, they saw bruises all over his body.

“The bruises just stood out. They could not cover it up. For us, for me, the evidence that he had been tortured came out.”

An inquest was held in 1970, and nobody was found to have been responsible for his death. The falling down steps theory was found to be the most likely cause of death.

“We have had to contain this. To bear this. You bottle up this thing. You don’t express it to friends; you don’t express it to your closest family,” said Muhammed of the lasting emotional impact.

He said 30 000 people attended his father’s funeral. On the same day, they felt the tremors from the terrible earthquake in Tulbagh.

For many Capetonians of that era, the Tulbagh earthquake is always associated with the death of the imam, and the enormous impact the atrocity has had on them.

But the family’s trauma was not over. They lost their house due to a nephew’s interpretation of Islamic law because, at the time, marriages under the Muslim faith were not officially recognised. They lived with family and friends, and his mother, Galiema, already a seamstress, got a job as a cleaner to support them, in addition to doing housework and looking after young children. She eventually saved and built them a new house.

Mohammed said the siblings tried to buy the house back to turn it into a centre of memory, but when relatives got wind of this, they sold it to someone else, and it was on sale until the price was out of their reach.

They had already been evicted from Claremont during apartheid before moving to that house, so it meant a lot to them.

Asked what the family would like from the inquest, he said they would like the finding that he fell down steps declared a lie.

They wanted all of the Security Branch police officers involved to be posthumously found guilty of intentional torture and calculated murder. He said the family also wanted the doctors, the inquest magistrate, and anyone else involved in the cover-up to be posthumously stripped of their qualifications, and their actions to be declared punishable conduct.

The only surviving policeman associated with Haron’s incarceration and death, Johannes Hendrik Hanekom Burger, will also testify. He was a cell guard.

The inquest continues on Friday.

News24